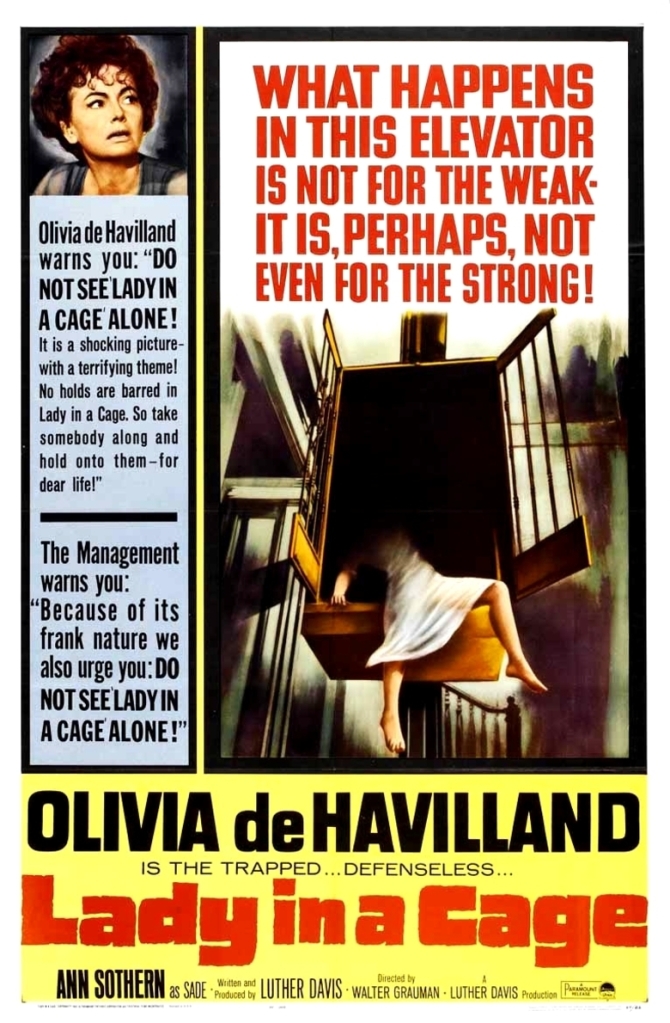

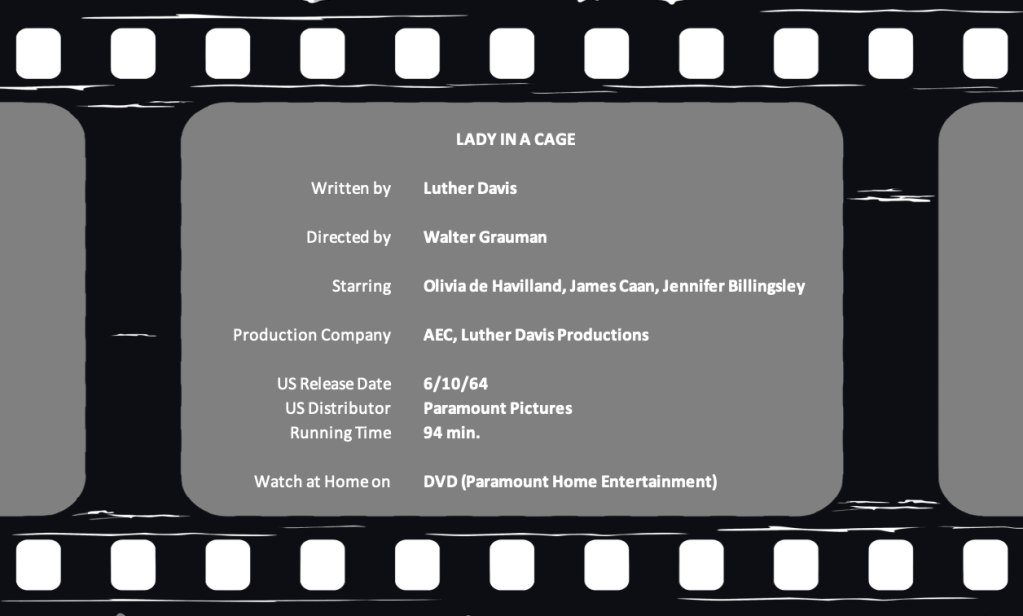

When I can’t locate mentions in my collection of vintage monster magazines or horror movie reference books, I like to find original reviews of a movie from when it was first released in theaters. I wouldn’t say this usually uncovers anything earth-shattering; however, in the case of Lady in a Cage (1964), two reviews indicate an initial reaction to the film that contradict the opinions of 2,908 people on IMDb that give the movie an average 6.8 rating.

On the last day of the year in 1963, someone at the trade paper, Variety, wrote:

There’s not a single redeeming character or characteristic to producer Luther Davis’ sensationalistically vulgar screenplay (based on a novel by Robert Durand.) It is haphazardly constructed, full of holes, sometimes pretentious and in bad taste.

A few months later, on June 11, 1964, A.H. Weiler wrote for the New York Times in a review titled, Aimless Brutality:

Since shock is a solid screen staple, the Lady in a Cage, which was exposed yesterday at the Embassy, 52d Street Trans-Lux and other theaters, eminently fills a grisly bill. But the seemingly grim troupe that fashioned this sordid, if suspenseful, exercise in aimless brutality merely appears to be made up of cynics without a point of view.

Wow; they really did not like this movie. What’s worse, it inspired a follow-up editorial in the New York Times 10 days later in which Bosley Crowther called it “socially hurtful” and reprehensible. At first glance, this might indicate that Lady in a Cage was ahead of its time, at least in terms of subject matter. Surely by today’s standards it seems tame. However, I have to wonder if the lack of a moral statement is part of the point of the movie.

The horrific events, taking place in a city where everyone is too busy to notice Mrs. Cornelia Hilyard’s (Olivia de Havilland) alarm bell when she’s trapped within her home elevator, are a comment on selfishness and a complete lack of social conscience. During a time when people defiantly refuse to wear masks to protect not themselves, but others, the idea is eerily prescient. Perhaps mid-60’s America didn’t yet want to admit this about themselves.

But perhaps screenwriter and producer Luther Davis did. Perhaps he peered into the seedy underbelly of the city and saw a little girl rolling her skate on a homeless man’s leg as he lay among the trash on the street. Perhaps director Walter Grauman imagined the scenes of everyday horror and translated them to the screen, showing a dead dog lying in the street as cars speed past it. Not acknowledging something doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

There’s even a bit of irony. Cornelia Hilyard presents herself as prim and proper. She’s exasperated when no one magically appears to help her. However, she also seems to be one of those selfish people with a lack of social consciousness. When she’s finally able to confront one of her tormentors, she cries, “You’re one of the many bits of offal produced by the welfare state. You’re what so much of my tax dollars goes to the care and feeding of!”

Variety continues:

Had the basic premise – of an invalid woman trapped in her private home elevator when the power is cut off – been developed simply, neatly and realistically, gripping dramatic entertainment might have ensued. But Davis has chosen to employ his premise as a means to expose all the negative aspects of the human animal. He has infested the caged woman’s house with as scummy an assortment of characters as literary imagination might conceive.

The author highlights one of the pitfalls of film criticism by writing, “had the basic premise…” and “but Davis has chosen…” Well, the basic premise is not what the author wanted or expected, and the creators of the film chose to make what they wanted. This doesn’t make a film inherently bad; it just means you may or may not like it. In these reviews, the critics don’t acknowledge simply that it doesn’t align with their personal tastes.

Lest I not practice what I preach, let’s remove the context and focus on the story and the filmmaking. It’s a great set-up and one that’s been used time and again in films from Wait Until Dark (1967) to Hush (2016.) In these, a physically restricted person is trapped in a situation where he or she must overcome their helplessness to survive. Cornelia Hilyard isn’t blind or deaf, but she is recovering from hip surgery and is trapped in… a cage.

Lady in a Cage also arrived after the birth of the hagsploitation sub-genre with films like What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) and Hush… Hush Sweet Charlotte (1964), in which de Havilland also stars, and it’s a precursor to the home invasion sub-genre which has exploded in recent years. I’m not saying there wouldn’t be The Strangers (2008) without it, but that the idea of being terrorized in your one safe place, your home, has apparently been a collective fear or ours for decades.

This is all to say, again, that I find these concepts compelling and it’s hard to not produce suspense from the situation, regardless of how “reprehensible” the characters may be. On that note, don’t we want the bad guys to be bad guys? Must we have a good guy among them to counter their seemingly senseless violence? The utter hopelessness of it all is what generates the drama and, again, the suspense.

This was the big-screen debut of James Caan. I bet those critics that hated the movie at least praised his performance. Uh… no:

Caan, as the sadistic leader of the little rat pack, appears to have been watching too many early Marlon Brando movies. Variety

and

James Caan as the youthful bestial leader of the gang, is a laconic hoodlum who is crudely aping Marlon Brando, an adequate derelict. New York Times

Oh, so there are different levels of derelict, Marlon Brando being a merely “adequate” one.

The follow-up editorial in the New York Times is required reading. Crowther addresses the comments I made about film writers and criticism for which they are and are not responsible. He perhaps draws a different conclusion than I do. However, my conclusion is, and always has been, that a movie’s primary responsibility is to elicit emotion and thereby entertain its audience. That’s all Lady in a Cage needs to do, and I think it does it extremely well.

Leave a comment